Have you ever wondered why almost all classical music composers are white males? When I was a teenager in The Old Country, I wondered about it too from time to time, but I suppose because I was also a white male it didn’t bother me much. Of course, that was a good many years ago and the world was a different place. Even so, I am sure that even today, many young people who become involved in classical music wonder the same thing, especially if they are black girls.

We know some of the reasons for the absence of women among European classical composers and here I use the word “classical” in its broader sense. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, women were generally not encouraged to enter the male-dominated musical profession on the grounds that they probably wouldn’t have been taken seriously, especially if they were composers. The only musical niche where women were encouraged was in singing. Of course, there have been always been women composers. Ironically, one of the first notable medieval composers was a woman – and a remarkable one too.

She was a Benedictine abbess born in 1098 who became known as Hildegard von Bingen. She was a writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary and polymath. Today she remains one of the best-known composers of early sacred monophony. In 1136, she was elected magistra (Mother Superior) of her convent and later founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg and Eibingen. Hildegard wrote theological, botanical and medicinal works, as well as poems and music for the liturgy. There are more surviving works by Hildegard than by any other composer from the Middle Ages, and she is one of the few composers to have written both the music and the words. She is also regarded as the founder of scientific natural history in Germany. From childhood, she began to receive “visions” which she called the umbra viventis lucis, the “reflection of the living Light”.

During the Baroque, a handful of women composers achieved recognition, notably Barbara Strozzi, Francesca Caccini and the oddly reclusive Isabella Leonarda who spent most of her life in a convent. The 19th century brought us the talented Fanny Mendelssohn, elder sister of Felix. From a well-to-do family, she wrote chamber music, over a hundred piano pieces and well over two hundred songs. And here’s an interesting thing. Because of family wishes and the social conventions, some of her pieces were published under her brother’s name. If I’d been her, I would not have been very pleased. Not very pleased at all. Music historian Angela Mace Christian reports that Fanny Mendelssohn “struggled her entire life with the conflicting impulses of authorship versus social expectations.”

One of the most influential women musicians in the 19th century was the child prodigy Clara Wieck who later became the wife of composer Robert Schumann. In her day, Clara Schumann was best known as a pianist and teacher but she wrote an enormous amount of music. During her lifetime it was largely ignored and even her husband seemed to be ambivalent about her composing activities.

Teresa Carreño was a Venezuelan pianist, singer and composer born in 1853. She performed for Abraham Lincoln at the White House in 1863 and at several of Henry Wood’s promenade concerts in London. Carreño composed several dozen piano works and in 1991 received the posthumous if slightly bizarre distinction of having a Venusian crater named in her honour. The organisation crisply entitled International Astronomical Union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature decided in their collective wisdom that Venusian craters should be named after famous female Earthlings. If there weren’t enough, female first names would do. Other musicians who received this curious honour were Nadia Boulanger, Kirsten Flagstad, Kathleen Ferrier, Wanda Landowska and Clara Wieck. There are 900 named craters on Venus; though only a small proportion of the total number.

The first American woman composer who achieved international recognition was Amy Beach; a prolific writer, an accomplished concert pianist and one of the most respected and acclaimed American composers of her era. Florence B. Price was another early American female composer but also happened to be African-American. This symphonic work therefore has a special significance.

Florence B. Price (1887-1953): Concerto in One Movement. Lulu Liu (pno), Texas Medical Center Orchestra cond. Libi Lebel (Duration: 17:18; Video: 1080p HD)

From the opening notes of this concerto, you can hear an original, distinctive voice. Florence B. Price was born in Arkansas and after high school she enrolled in the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. Initially, she chose to pass as Mexican, to avoid the then discrimination against African Americans. She became profoundly religious and often brought church music into her work. She wrote an impressive number of compositions including four symphonies, four concertos and a large collection of other pieces. Although described as a “concerto in one movement”, there are three distinct sections. After a passionate first section with its yearning melodies, there’s an achingly beautiful central section; a pensive movement which seems to have its roots in African-American folk melody. The sunny and light-hearted third section has echoes of the cake-walk and minstrel shows. This is a gorgeous work: lovely, unselfconscious music brimming with life.

In case you’re wondering, the Texas Medical Center Orchestra is one of the few orchestras in which most of the members are health professionals. Along with their conductor Libi Lebel and piano soloist Lulu Liu, they provide an exhilarating performance of this heart-warming work.

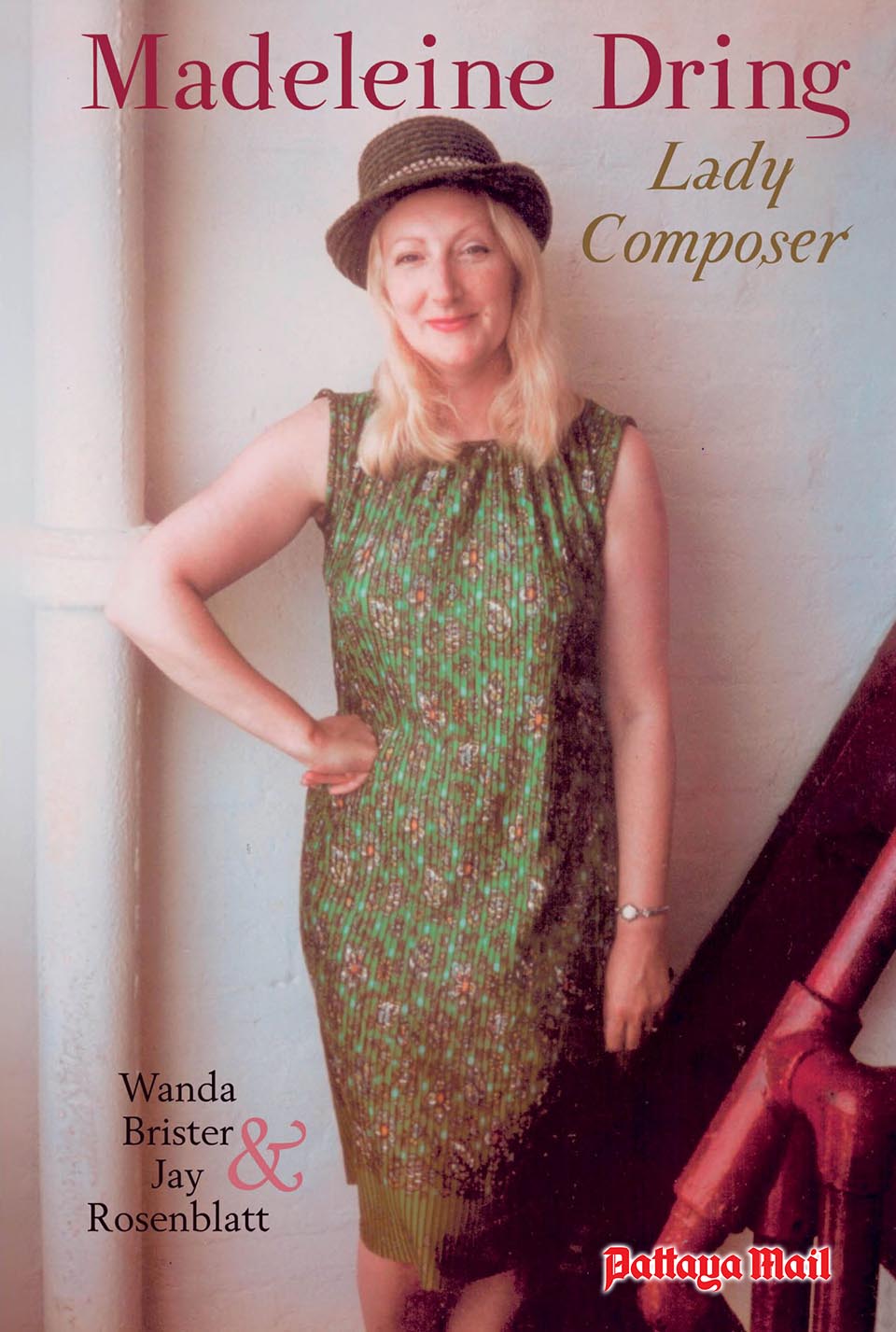

Madeleine Dring (1923-1977): Trio for Flute, Oboe and Piano. Hollie Macdonald (flt); Sam Baxter (ob); Zi Wang (pno) (Duration: 11.25; Video: 1080p HD)

Madeleine Dring was a respected name among British composers though she chose not to compose large-scale works but instead pieces for solo piano, piano duets, songs with piano and some chamber music. She was an immensely prolific composer and despite her preference for chamber music also wrote a one-act opera, two ballets, four dance dramas and incidental music for television.

She began composition studies at the age of ten at London’s Royal College of Music and was later taught by Sir Percy Buck, Herbert Howells and occasionally by Ralph Vaughan Williams. In 1947 she married the well-known oboist Roger Lord who for over thirty years was Principal Oboist with the London Symphony Orchestra. She composed several works for him, including the highly regarded Dances for Solo Oboe. Her music remains popular to this day, especially with oboe players.

Dring particularly enjoyed the musical style of Poulenc and jazz idioms. This charming trio was composed in 1968 and certainly has French overtones: it’s chromatic music but falls easily on the ear. The lively and rhythmic first movement contrasts with the short, pastoral slow movement with its oboe and flute solos and its darker middle section. The finale begins almost angrily and leads into a merry cadenza for the woodwinds before the audacious, spiky mood returns to drive the work to its snarling ending.

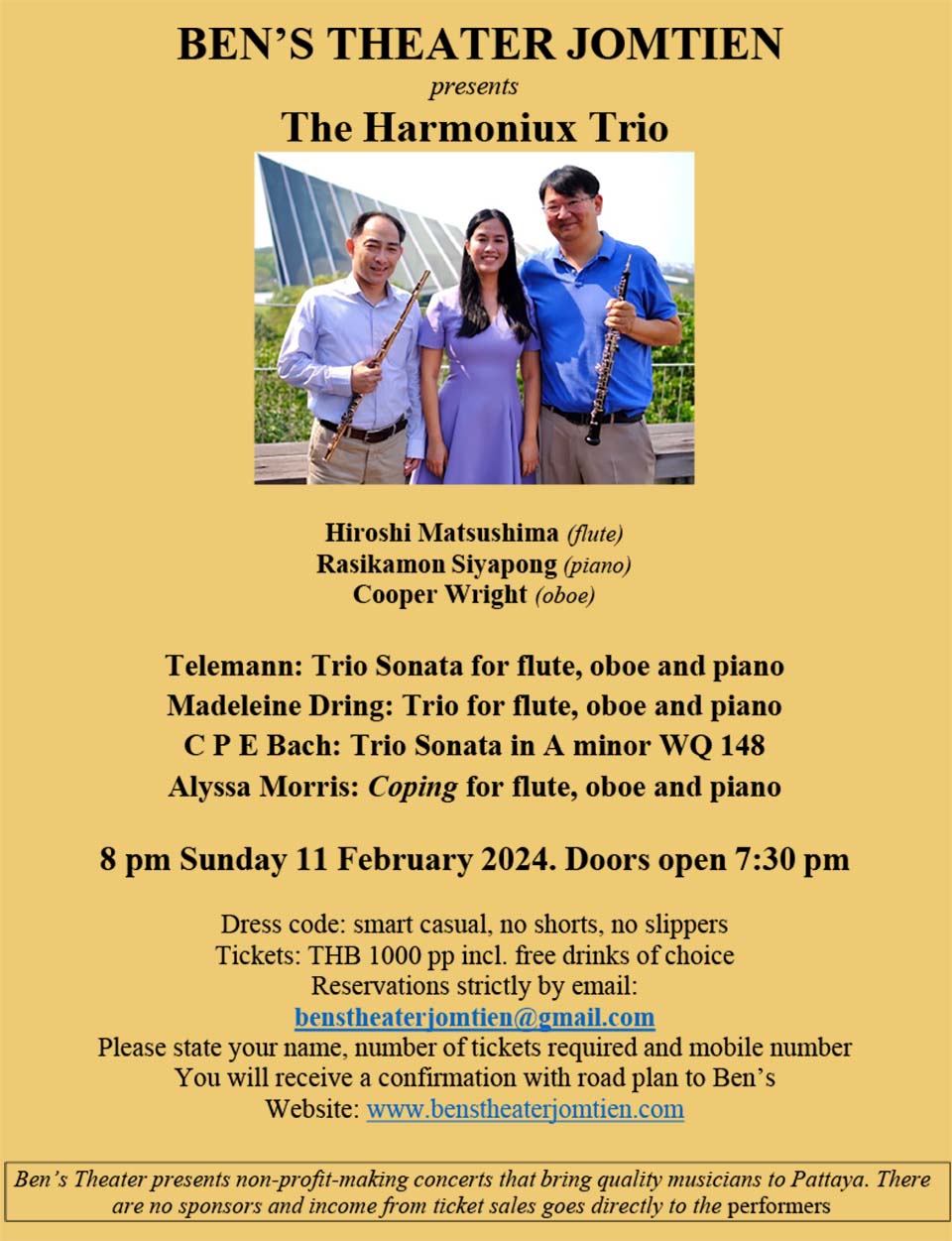

If you enjoyed this delightful work by Madeleine Dring, you can hear a live performance of it on Sunday 11th February at Ben’s Theater, Jomtien.