In a 1926 edition of the iconic French music magazine La Revue Musicale, an article opened with the line “Jazz truly rules the world.” Of course, this was during The Roaring Twenties but even then, it was probably an over-statement. However, it’s true that he twenties and thirties saw a significant influence of jazz on the work of some “classical” composers. During that time, Paris became a haven for many African-American jazz musicians as well as a coterie of European artists, writers and composers. Anyone who was someone in the art world showed up in Paris sooner or later. And perhaps because the distinctive sounds of jazz came as such a relief after the grim war years, many composers were all too eager to absorb them into their own music.

One such musician was the French Darius Milhaud, who travelled to New York to seek out jazz, which had long since spread from its New Orleans homeland. In Harlem, Milhaud was delighted to hear authentic jazz on the streets. It left a lasting impression and elements of jazz found their way into his music, notably the orchestral work La Création du Monde. For American composers, jazz was right on their doorstep. George Gershwin’s professional background was in popular music but he used jazz elements in works like Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990): Piano Concerto. Bennett Lerner (pno), New York Philharmonic cond. Zubin Mehta. (Duration: 17:37; Video: 480p)

Copland was a pioneer of the evocative American orchestral style that conjures up visions of sweeping prairies and open skies. He sometimes borrowed ideas from jazz, most famously perhaps in his 1949 Clarinet Concerto written for the jazz star Benny Goodman. Twenty years earlier, Copland experimented with jazz and ragtime in his Piano Concerto, described by one writer as being “dotted with blue notes”.

The work was first performed in 1927 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Koussevitzky with the composer as the soloist. It was not a great success. Perhaps Copland’s early music was a bit astringent for Bostonian ears, or perhaps the audience were listening for something that wasn’t there. In the second part of the Concerto, the eccentric, sardonic and sometimes downright weird ragtime style upset the Boston audience and critics. The work remained virtually unperformed for the next thirty years despite the fact that there are many charming moments and even hints of Gershwin, whose Rhapsody in Blue was completed two years earlier.

This lively performance was recorded in 1985 with a rather young-looking Zubin Mehta conducting the New York Philharmonic and the brilliant pianist Bennett Lerner who has lived in Thailand since 1990 and is a lecturer in the Music Department of Payap University in Chiang Mai.

Stravinsky’s interest in jazz dates back to his so-called Russian period, where hints of it appeared in The Soldier’s Tale and Ragtime for Eleven Instruments. In 1945 he began work on his Ebony Concerto for solo clarinet and jazz orchestra, commissioned by the well-known jazz-band leader, Woody Herman. Some controversy surrounds the origin of the work. The word was put about that Stravinsky was an admirer of Woody Herman and his Band, when in reality the composer had almost certainly never heard of them.

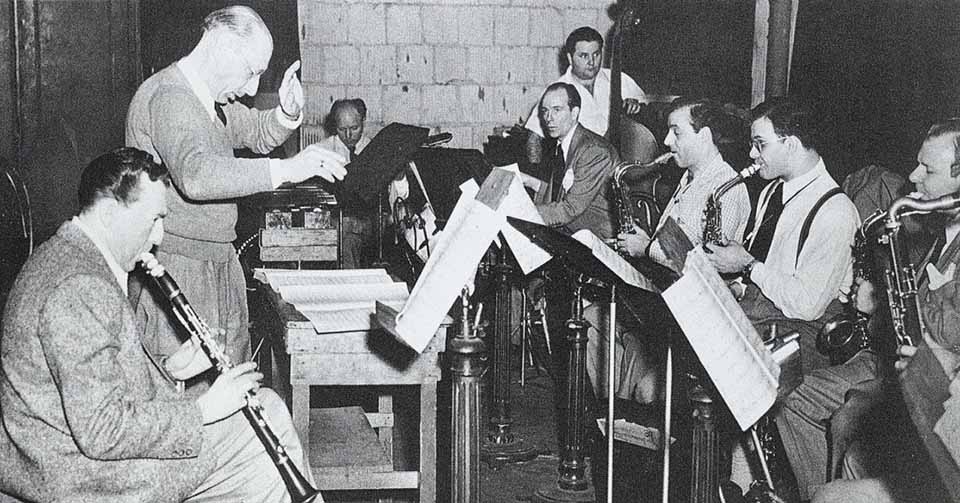

Over the years, I have studied and listened to Stravinsky’s works supposedly inspired by jazz or ragtime and come to the conclusion that he has not succeeded in capturing the spirit of either. Perhaps it was not his intention. Nevertheless, the works are attractive, approachable and written in a unique style that could only be Stravinsky. The Ebony Concerto is about as far removed from jazz as you could get. There are passages that resemble Eastern European folk songs or even Russian circus music. Woody Herman was disappointed in the work and found the solo clarinet part frighteningly difficult. During rehearsals with the composer, held backstage at New York’s Paramount Theatre, it became embarrassingly evident that neither Herman nor his band had the sight-reading ability to play the music. But after a great deal of rehearsal, they eventually gave the premiere at Carnegie Hall in 1946. You can find this performance on YouTube and while the musicians make a brave stab at the challenging music, it sounds awkward and stilted. The more recent performance by players from the LSO with Simon Rattle is far more successful. They may not be jazz musicians but to my mind, this curious but oddly attractive work is probably better served by those who are not.

|

|

|