Last week I was trawling the classical music groups on Facebook and came upon this extraordinary statement, “Life is like a piano; the white keys represent happiness and the black show sadness. But remember that both keys played together create sweet music.” You need only a few seconds to realize that this is irrational nonsense but judging from the “thumbs-up” icons, many gullible people appreciated it.

There are several slightly different versions of the statement circulating on the web, sometimes superimposed against an artistic background in an attempt to add a bit of gravitas to what is essentially fatuous rubbish. I even found the same pseudo-proverb solemnly quoted on a Christian website as though the statement has some profound, sacred meaning. If people are daft enough to believe this kind of nonsense it’s up to them. But what worries me is that children or teenagers reading it could have their concepts completely distorted. It happened to me once.

When I was a child in primary school, our teacher once wanted to demonstrate the speed at which Earth is rotating. He reached out to the large globe on his desk, causing it to rotate at such a speed that the continents were a blur. “Earth is rotating even faster than that,” he announced. I was not a particularly bright child, but I could see that something was seriously wrong with this statement. I plucked up the courage to ask that if the world were really spinning like that, why was it that the sun and moon appeared almost stationery in the sky. The teacher didn’t have an answer. This dilemma troubled me for about a year until I finally realized why the teacher had got it wrong. Nevertheless, this well-minded but misguided teacher succeeded in screwing up my conceptual thinking.

Many years later, I was observing a music teacher earnestly telling her class that the notes A and C produce “a sad sound” whereas the notes A and C sharp produce a “happy” sound. This of course is complete nonsense, and with as much tact as I could muster, I told her so. It concerned me, partly because the statement was simply false and partly because the children were being fed an over-simplistic notion that music is either happy or sad. We all know that music encompasses far richer and more powerful emotions that these two childish words can ever express. Sometimes it defies description completely. As the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen wrote, “Where words fail, music speaks.”

But let’s return for a moment to the half-witted idea that white keys represent happiness. In the 18th century, the colours of the keys on pianos and other keyboard instruments were exactly reversed. The white keys were black and the black keys were white. That rather renders the pseudo-proverb a bit meaningless. In any case, individual notes on the keyboard do not carry any emotional quality. And what, we ask is “sweet music” supposedly created when a black note and a white note are played together? If you play the “white” note “A” with the adjacent “black” note G sharp the sound is anything but “sweet”. The sound produced by the two “white” notes F and B is known technically as a tritone and during the Middle Ages this combination of notes was associated with evil. It was often described as Diabolus in musica – the devil in music.

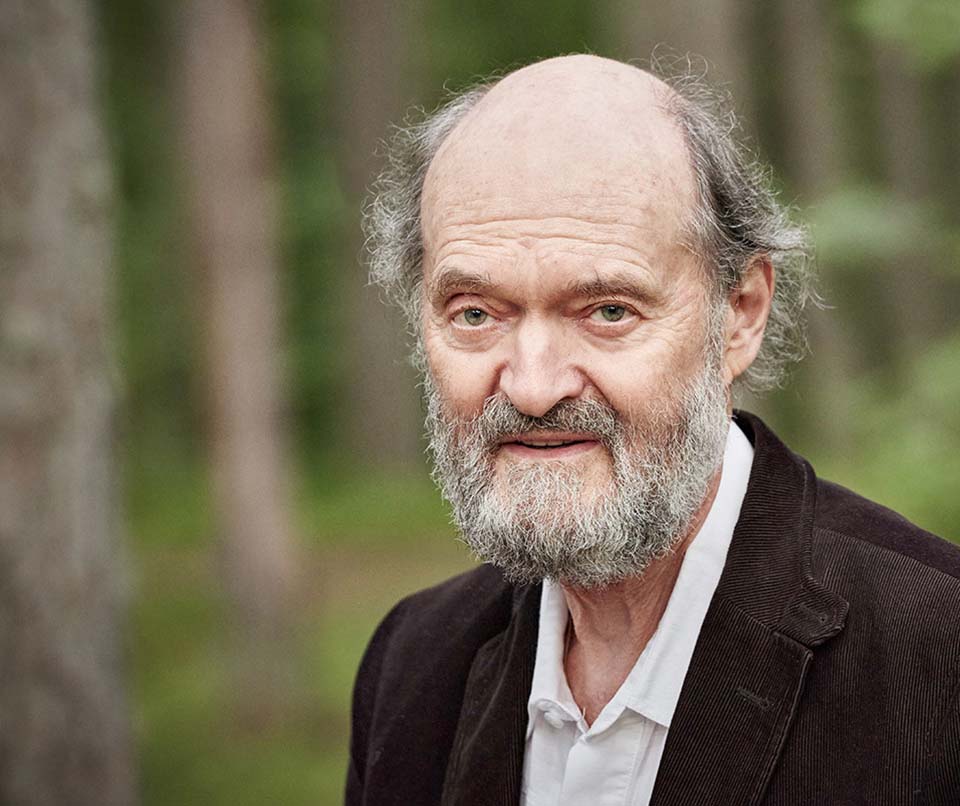

Anyway, the notion of musical sounds that defy emotional explanation reminds me of the recent works of the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt whose music, some writers have claimed, “speaks to everyone.”

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935): Spiegel im Spiegel for Cello and Piano. Leonhard Roczek (vlc), Herbert Schuch (pno). (Duration: 10:27; Video: 720p HD)

Initially Pärt was influenced by Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Bartók but later he went through a long period of creative and contemplative silence absorbing himself in plainsong and Gregorian chant. Spiegel im Spiegel (“mirrors in the mirror”) dates from 1978 and uses a personal style of writing that Pärt named tintinnabuli, influenced by the composer’s mystical experiences with chant music. It signified a new minimalist simplicity but it’s based on a unique system of rules linked with Orthodox and Gregorian aesthetics. The melodic elements float upwards and downwards, sometimes moving only slightly before beginning a new motion in a different direction.

On the surface the music seems simplicity itself: slow repeated arpeggios in F major from the piano and fragments of floating sustained melody from the cello moving from one note to the other. However, beyond the notes, the music is far more structured than it appears. It takes us far beyond simple notions of happiness or sadness into realms of experience which are almost indescribable and somehow unsettling. Yet this is a work of incredible beauty that seems to touch the eternal. It might even appear to reach right inside you and speak to the very essence of your being. This music can produce an incredibly powerful inner experience and for reasons they cannot describe, it brings many people to tears. When the music abruptly closes, the emptiness and sudden silence are almost painful.

|

|

|