The famous American photographer Ansel Adams has been dead for 24 years, but his influence on photography as an “art form” will probably be with us forever. Particularly Black and White, which is rapidly reaching “art” status all the time.

Adams was born in San Francisco in 1902, but his early interest was in music and the piano, which he initially hoped to develop into a professional career. However, as a 14 year old in 1916 he took his first photographs of the Yosemite Valley, an experience of such intensity that later reviewers of the Ansel Adams history recorded that he was to view it as a lifelong inspiration.

The Yosemite Valley would probably not be as well known world-wide as it is, if it were not for Adams, who returned every year thereafter to record its grandeur. During these trips he became even more in love with nature and its conservation and became associated with the Sierra Club in 1920.

In 1927 he published his first portfolio, ‘Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras’, and the following year he became an official photographer for the Sierra Club.

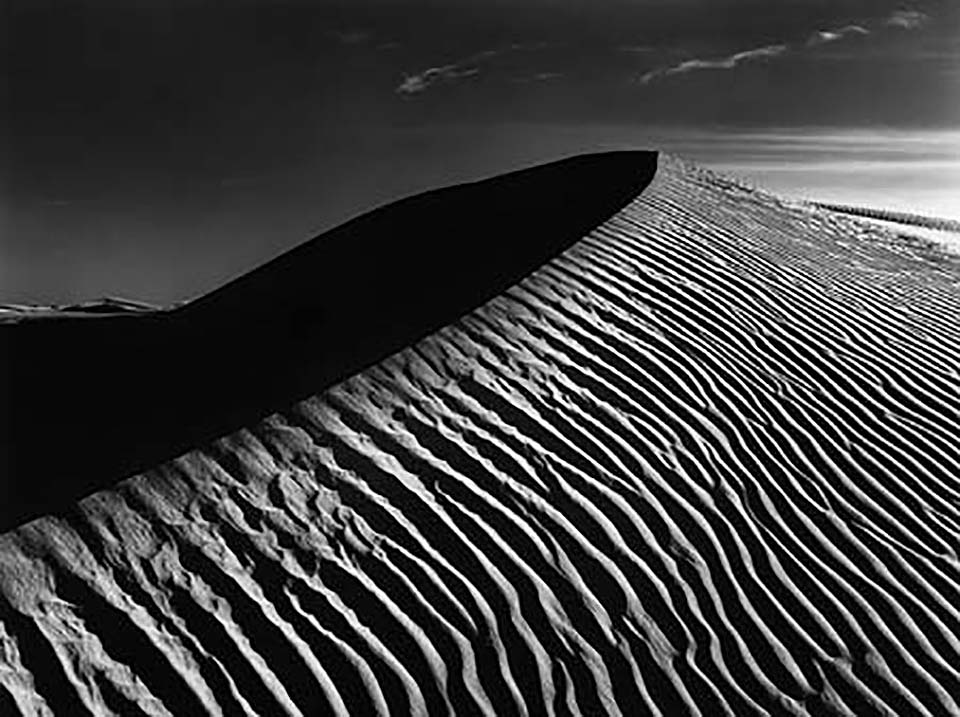

Like all photographers, Adams was interested in the work of others and was influenced by the straight photography of Paul Strand, and the works of Steiglitz, Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham. It was with the latter two photographers that he formed the Group f 64. For Adams and Weston especially, the f 64 philosophy embodied an approach to perfect realization of photographic vision through technically flawless prints. Even the use of the name f 64 shows the depth of field concept seen in so many of Adam’s photographs – sharp from front to back. Although the concept of the Zone System had not been finally formulated, you could see the beginnings of this at that time in the early 1930’s.

In 1935, Adams first book on photographic technique was published and by then he was giving one-man exhibitions in America. Moving to the Yosemite Valley, he continued to photograph the natural wonders and many of his images were published in the 1938 publication of Sierra Nevada – The John Muir Trail.

With the advent of WWII, Adams went to work for the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. During this time he began to develop a codification of his approach to exposure, processing, and printing – this became the Zone System. In effect, this system aimed at pre-visualization of the final print. In other words, you, the photographer know the result you want, and by application of the Zone System, you can make it happen (though this is not necessarily easy).

Adams said conventional photographic recording, was “acceptable though perhaps uninspired” and created the phrase “acute and creatively expressive.” In the Zone System, he engineered a technique by which the photographer could manipulate the photograph’s internal tones. By means of filtration, development, and print controls, contrast could be heightened or softened and the placement of object values along the tonal scale could be predetermined by the photographer before the shutter was released. Yes, he used a notebook to record the details he would later print out so faithfully in his dark-room.

After the war, Adams moved into lecturing as well as continuing to photograph. He also developed a knowledge of the techniques of photographic reproduction to assure that the quality of any reproduced work might approach, as closely as possible, the standard of the original print.

His place in the photographic halls of fame were by then assured, following his award of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1948 to photograph national park locations and monuments. More books on photography were written, and his stature continued to increase within the Fine Arts circles. By 1966 he had been elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and by the late 1970’s his prints were being sold to collectors for prices never equaled by any living American photographer.

We should all aspire to perfection and I give you three Ansel Adams quotes:

“You don’t take a photograph, you make it.”

“A good photograph is knowing where to stand.”

“The single most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.”

|

|

|