Mashpee, Mass. (AP) – The Massachusetts tribe whose ancestors shared a Thanksgiving meal with the Pilgrims nearly 400 years ago is reclaiming its long-lost language, one schoolchild at a time.

“Weesowee mahkusunash,” says teacher Siobhan Brown, using the Wampanoag phrase for “yellow shoes” as she reads to a preschool class from Sandra Boynton’s popular children’s book “Blue Hat, Green Hat.”

“Weesowee mahkusunash,” says teacher Siobhan Brown, using the Wampanoag phrase for “yellow shoes” as she reads to a preschool class from Sandra Boynton’s popular children’s book “Blue Hat, Green Hat.”

The Mukayuhsak Weekuw – or “Children’s House” – is an immersion school launched by the Cape Cod-based Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, whose ancestors hosted a harvest celebration with the Pilgrims in 1621 that helped form the basis for the country’s Thanksgiving tradition.

The 19 children from Wampanoag households that Brown and other teachers instruct are being taught exclusively in Wopanaotooaok, a language that had not been spoken for at least a century until the tribe started an effort to reclaim it more than two decades ago.

The language brought to the English lexicon words like pumpkin (spelled pohpukun in Wopanaotooaok), moccasin (mahkus), skunk (sukok), powwow (pawaw) and Massachusetts (masachoosut), but, like hundreds of other native tongues, fell victim to the erosion of indigenous culture through centuries of colonialism.

“From having had no speakers for six generations to having 500 students attend some sort of class in the last 25 years? It’s more than I could have ever expected in my lifetime,” says Jessie “Little Doe” Baird, the tribe’s vice chairwoman, who is almost singularly responsible for the rebirth of the language, which tribal members refer to simply as Wampanoag (pronounced WAHM’-puh-nawg).

Now in its second year, the immersion school is a key milestone in Baird’s legacy, but it’s not the only way the tribe is ensuring its language is never lost again.

At the public high school, seven students are enrolled in the district’s first Wampanoag language class, which is funded and staffed by the tribe.

Up the road, volunteers host free language learning sessions for families each Friday at the Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Museum.

And within the tribe’s government building – one floor up from the immersion school – tribal elders gather twice a week for an hour-long lesson before lunch.

“Sometimes it goes in one ear and out the other,” confesses Pauline Peters, a 78-year-old Hyannis resident who has been attending the informal sessions for about three years. “It takes us elders a while to get things. The kids at the immersion school correct us all the time.”

The movement to revitalize native American languages started gaining traction in the 1990s and today, most of country’s more than 550 tribes are engaged in some form of language preservation work, says Diana Cournoyer, of the National Indian Education Association.

But the Mashpee Wampanoag stand out because they’re one of the few tribes to have brought back their language despite not having any surviving adult speakers, says Teresa McCarty, a cultural anthropologist and applied linguist at the University of California Los Angeles.

“Imagine learning to speak, read, and write a language that you have never heard spoken and for which no oral records exist,” she says. “It’s a human act of brilliance, faith, courage, commitment and hope.”

Jessie Baird was in her 20s, had no college degree and zero training in linguistics when a dream inspired her to start learning Wampanoag in the early 1990s.

Working with linguistic experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other tribal members, Baird developed a dictionary of Wampanoag and a grammar guide.

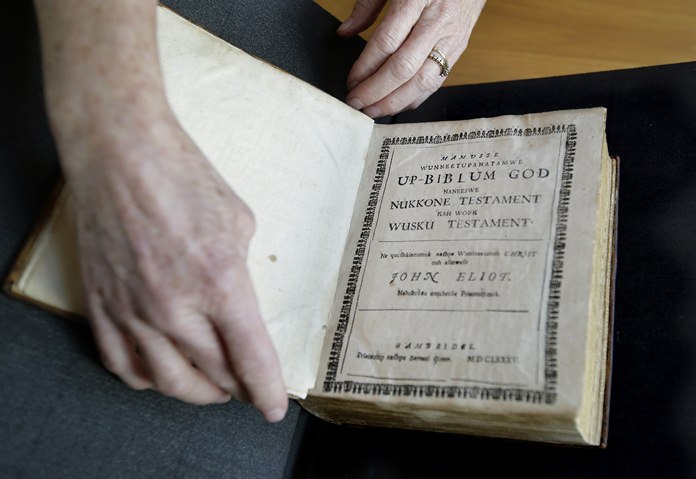

She and others drew on historical documents written in Wampanoag – including personal diaries of tribal members, Colonial-era land claims and a version of the King James Bible printed in 1663 that is considered one of the oldest ever printed in the Western hemisphere.

To fill in the gaps, they turned to words, pronunciations and other auditory cues from related Algonquian languages still spoken today.

The work landed Baird at MIT, where she earned a graduate degree in linguistics in 2000 and a prestigious MacArthur Foundation genius grant in 2010.

Nearly three decades on, the tribe is still in need of more adults fluent in the language to continue expanding its immersion school and other youth-focused language efforts – the keys to ensuring the language’s survival, says Jennifer Weston, director of the tribe’s language department.

The school currently enrolls pre-K and kindergarten-age children but hopes to ramp up to middle school within five years.

“The goal is really to have bilingual speakers emerge from our school,” Weston says. “And we’ve seen from other tribal communities that if you want children to retain the language, you have to invest in elementary education. Otherwise the gains just disappear.”