The impetus for this week’s column came from the rock concert during the Burapha Bike Week. This was the real deal in rock music, with our local musicians playing with a current international (Guns ‘n Roses) guitarist (but not Slash, I am sorry to say).

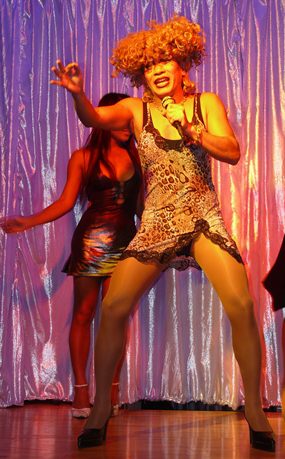

Now stage photography can be quite a specialized art form, with many stage acts having their own photographers who tour the world with them, just to get those iconic shots of the stars performing on stage. However, you can do just the same though on a smaller scale.

Have you ever visited Walking Street and counted the number of live bands? The Pattaya Players thespians are another source of stage subjects. There is even Likay or similar Thai productions.

As opposed to portraits, with on-stage photography, you are not in control of the model in any way at all. You also have some very difficult composition and lighting problems to contend with. You cannot quite ask someone in the middle of Caesar’s death bed scene to hold that pose and say “Cheese”. Mick Jagger will also not stop for you to focus while running frenetically from one side of the stage to the other.

The lighting, too, is quite different from that you normally experience. Stage lighting is generally tungsten based and sharp (what we call “spectral” lighting). Spots for the performers and floods for the background are the hallmarks of the usual stage lighting. The use of spots in particular is used to highlight the principal performer or action on stage.

Successful “stage” photographs have managed to retain that “stagey” lighting feel to them, so that instantly you look at the image you know it is of a performer on a stage somewhere. Remember, that as a photographer you are recording events, people and places as they happen. You are a mirror of the world!

The secret of retaining that stage feel is in the lighting. Because it tends to be dark, the first thing the average photographer will do is to bolt on his million megawatt flash gun with enough power to light up the far side of the moon. While understandable, that is not the way.

Do you use a telephoto lens? No. Because it gets you too far from the light falling on the performers. Again it is the old adage of “Walk several meters closer” for this type of photography too. Use a standard lens and get close as possible. If needs be, find which row seat you need to be able to do this. All part of being prepared.

Now in the good old ‘film’ days, you got hold of some “fast” film. 800 ASA if you could, but 400 ASA would do. However, with today’s digital cameras, you can safely dial in 800 ASA or even more. If the image breaks a bit, don’t worry, it just adds to the “stage” feel.

So, what about lighting? Leave the flash in the bag, or turn it off at the camera. Now I know it is dark, but you are trying to retain the stage lighting effects. In other words, you are going to let the stage’s lighting technician be the source of light for your photographs.

Now get a seat as close to the action as you can, and then select a lens that can allow you to fill the frame with the performers. Funnily enough, that will be, in most cases, the ‘standard’ 50 mm lens. Shots that show an entire dark stage with two tiny little people spot lit in front are not good stage shots. In fact they are not good anything shots! If all you have is a fixed lens point and shooter, get as close to the front of the stage as you can. You can still get the scene stopping shot – you have just to get very close. OK?

There is no real ‘problem’ with white balance with digital cameras. You will still get an image that says “stage performance”, which is what you want, never mind the colors.

Next time you are getting shots of people on stages, turn the flash off, and you will see the end result is much better.