With the start of a new year, I sat down fully intending to write a column about having a photo project to spark up your enthusiasm for using your camera – after all it can capture many more things than just Thai women posing (which they do instantly at the removal of a lens cover)!

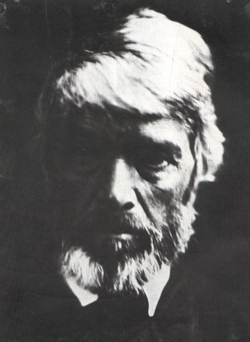

However, look at the photograph this week. Hardly a Thai lady posing, but that of the eminent historian Thomas Carlyle, taken in 1867 and is ranked as one of the most powerful portraits in the history of photography.

Look again – technically it is imperfect. There is blurring of the image, and when you realise that the shutter was open for probably around three minutes, then you can see why. The sitter could not possibly remain motionless for that period of time. But it has the power to mesmerize you. Why?

The dynamics of this shot come from the very first principles of photography – painting with light. It is not the subject that matters – it is the way you light the subject that matters. The light is falling on the sitter almost from the side and slightly above. One eye is partially lit and the other in shadow. The hair and beard show up strongly. The photo is totally confrontational.

Analyse further. If the face had been front lit, and both eyes, the nose and the mouth were all clearly visible then there would be no air of mystery. The dark areas of the photograph have made you look further into it. You begin to imagine what the features were like. You also begin to imagine what the person was like. You have just experienced the “perfect” portrait.

This photo was taken by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815 – 1879) a British lady who had been raised in India, in the days of the British Raj. Surrounded by servants, she had never had to do anything for herself, and yet, in her late forties she took up the new fangled notion of photography. This was not the age of the point and shoot simplicity we enjoy today. This was the age of making your own photographic plates by painting a mixture of chemicals all over it – chemicals you mixed yourself – exposing the plate in a wooden box camera and then fixing the negative in more chemicals and finally making a print.

It was the 29th of January 1864 when Mrs. Cameron finally produced her first usable print. She had made the exposure at 1 p.m. and in her diary recorded the fact that by 8 p.m. she had made and framed the final print. Somewhat different from today’s “instant” viewing!

As opposed to the tiny “cartes de visite” that were the norm at that time, Julia Margaret Cameron was making close up portraits 30×40 cm. However, she would not have managed to photograph so many of the notables of the era had it not been for her next door neighbour, the Poet Laureate, Alfred Lord Tennyson. After Tennyson saw his portrait he persuaded his eminent friends to sit for her as well. Most of these portraits were different from the Thomas Carlyle photograph in that they were taken in profile. Mrs. Cameron felt that the innate intelligence could be more easily seen in the profile and this may have been the result of the influence of the quasi-science of Phrenology, whereby your cranial bumps showed your true talents, which was all the rage at that time!

Julia Margaret Cameron contributed to photography by showing that it is the eye of the photographer that dictates the photograph, not the “smartness” of the equipment. She also showed a personal determination to succeed which should be an example to the young photographers of today.

So you can stop reading the photographic magazines to see if you should buy the latest offering from Nikocanonolta complete with one millionth of a second shutter speed and dedicated flash power for up to three kilometres and just go out and take photographs with what you have got. Look at what is in front of you and “make” your own photographs “work” for you. Thus endeth the inspirational lesson. Thank you Mrs. Cameron. Class dismissed!