Henri Cartier-Bresson was the originator of the phrase in photography, “The Decisive Moment.” Undoubtedly he was one of the great photographers of the 20th century. However, according to his biographer Pierre Assouline (Henri Cartier-Bresson: A Biography, Thames & Hudson) he was also a difficult and haughty individual with total confidence in his own artistic superiority.

He was born in France in 1908 and initially studied painting, following much of the Surrealist school of thought of the time. However, by the time he was 22 years old he had dropped art for photography, but began to apply the art concepts he had been exposed to towards photography.

Cartier-Bresson was never a technocrat. He used a Leica M4 or 3G, with the chrome covered with black tape to make the camera less conspicuous. He had one preferred lens, a 50-mm Elmar, the one that is closest to the view seen by the naked human eye.

Cartier-Bresson’s cameras had no automatic metering or autofocus, so you can see just how molly-coddled we are today. His set shutter speed was 1/125th of a second, so he only had to adjust the aperture to suit the light. His film stock was Kodak Tri-X rated at ISO 400 and detested the flash.

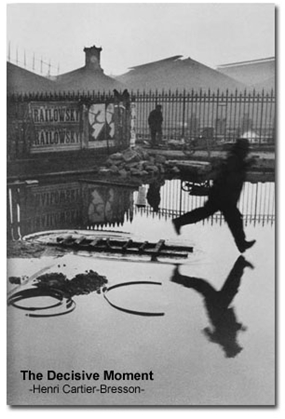

However, the ‘decisive moment’ was his to capture. This was explained by Cartier-Bresson in the foreword to his book, published in 1952, “Images a la Sauvette” (The Decisive Moment). He called it “The simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as the precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.”

The most challenging of Cartier-Bresson’s rules was that there should be no cropping of his images. As a photojournalist working on assignment for magazines, he reluctantly accepted the prerogative of the editor and designer to crop his photos, but he always detested the results. His composition in the Leica viewfinder was, in his opinion, perfect.

Early in his photographic career he observed that the interesting subject is not necessarily the parade, but the faces and actions of the spectators watching it. In 1937, he was sent to London by Ce Soir as part of a team to report on the coronation of George VI. Knowing that the others in the team would be faithfully recording the actual parade, he simply turned his back on it and took photographs of the expressions on the faces of the spectators watching it. This catching of the human expressions is one of the basics of photojournalism, of which Cartier-Bresson was the adjudged master.

Take a look at the classic photo to illustrate the decisive moment. The shot was taken in 1932 at the Place de l’Europe, where the marooned man has finally realized that there is no way out, and having made the decision, launches himself off the ladder. That split second, that decisive moment caught by Cartier-Bresson in such a way the viewer can feel the moment still today, 80 years later. In his words, “There was a plank fence around some repairs behind the Gare Saint-Lazare train station. I happened to be peeking through a gap in the fence with my camera at the moment the man jumped.”

He recorded the Spanish Civil War in the 1930’s and then WW II, but was finally captured and he became a POW. He escaped three years later, and was there to record the liberation of Paris from the Germans.

Of course, he was by that stage becoming an icon, and in 1947 joined forces with two other ground-breaking photojournalists, Robert Capa and David Seymour to form the Magnum agency. However, for Cartier-Bresson, news was much more than the photo-journalists were showing. It was necessary to get behind the scenes.

Cartier-Bresson and his confreres forged a name for hard hitting news photography. Cartier-Bresson covered Mao Zedong’s victory in China and the death in India of nationalist movement leader Mahatma Gandhi.

However, in 1975 he gave up photography and returned to painting.

In 2004, the world lost a photographer who had vision and the ability to record his vision in a way the world could understand. The decisive moment will always belong to Henri Cartier-Bresson.