Molly Porter & Megan Watzke

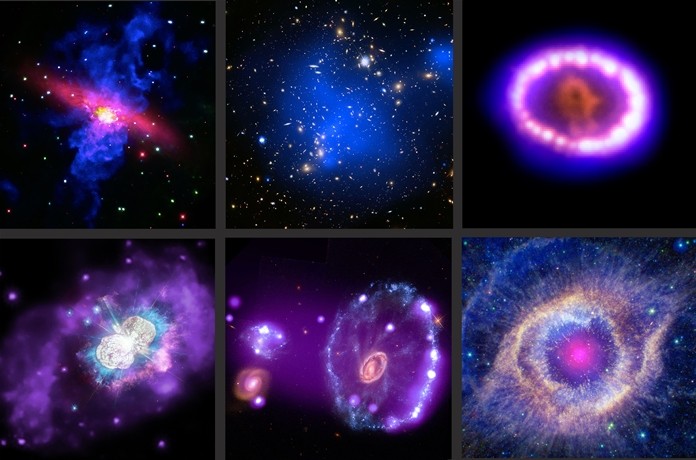

Humanity has “eyes” that can detect all different types of light through telescopes around the globe and a fleet of observatories in space. From radio waves to gamma rays, this “multiwavelength” approach to astronomy is crucial to getting a complete understanding of objects in space.

This compilation gives examples of images from different missions and telescopes being combined to better understand the science of the universe. Each of these images contains data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory as well as other telescopes. Various types of objects are shown (galaxies, supernova remnants, stars, planetary nebulas), but together they demonstrate the possibilities when data from across the electromagnetic spectrum are assembled.

Top row, from left to right:

Messier 82, or M82, galaxy

Credits: X-ray: NASA/CXC; Optical: NASA/STScI

Messier 82, or M82, is a galaxy that is oriented edge-on to Earth. This gives astronomers and their telescopes an interesting view of what happens as this galaxy undergoes bursts of star formation. X-rays from Chandra (appearing as blue – up & down – and pink – side to side) show gas in outflows about 20,000 light years long that has been heated to temperatures above ten million degrees by repeated supernova explosions. Optical light data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (red and orange – center) shows the galaxy.

Galaxy cluster Abell 2744

Credits: NASA/CXC; Optical: NASA/STScI

Galaxy clusters are the largest objects in the universe held together by gravity. They contain enormous amounts of superheated gas, with temperatures of tens of millions of degrees, which glows brightly in X-rays, and can be observed across millions of light years between the galaxies. This image of the Abell 2744 galaxy cluster combines X-rays from Chandra (diffuse blue emission) with optical light data from Hubble (red, green, and blue).

Supernova 1987A (SN 87A).

Credits: Radio: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), P. Cigan and R. Indebetouw; NRAO/AUI/NSF, B. Saxton; X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/PSU/K. Frank et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI

On February 24, 1987, observers in the southern hemisphere saw a new object in a nearby galaxy called the Large Magellanic Cloud. This was one of the brightest supernova explosions in centuries and soon became known as Supernova 1987A (SN 87A). The Chandra data (blue – outer ring) show the location of the supernova’s shock wave — similar to the sonic boom from a supersonic plane — interacting with the surrounding material about four light years from the original explosion point. Optical data from Hubble (orange and red – inner rings) also shows evidence for this interaction in the ring.

Bottom row, from left to right:

Eta Carinae

Credits: NASA/CXC; Ultraviolet/Optical: NASA/STScI; Combined Image: NASA/ESA/N. Smith (University of Arizona), J. Morese (BoldlyGo Instituts) and A. Pagan

What will be the next star in our Milky Way galaxy to explode as a supernova? Astronomers aren’t certain, but one candidate is in Eta Carinae, a volatile system containing two massive stars that closely orbit each other. This image has three types of light: optical data from Hubble (appearing as white center), ultraviolet (cyan – small band surrounding center) from Hubble, and X-rays from Chandra (appearing as purple emission – outer band surrounding both). The previous eruptions of this star have resulted in a ring of hot, X-ray emitting gas about 2.3 light years in diameter surrounding these two stars.

The Cartwheel galaxy

Credits: X-ray: NASA/CXC; Optical: NASA/STScI

This galaxy resembles a bull’s eye, which is appropriate because its appearance is partly due to a smaller galaxy that passed through the middle of this object. The violent collision produced shock waves that swept through the galaxy and triggered large amounts of star formation. X-rays from Chandra (purple) show disturbed hot gas initially hosted by the Cartwheel galaxy being dragged over more than 150,000 light years by the collision. Optical data from Hubble (red, green, and blue) show where this collision may have triggered the star formation.

The Helix nebula

Credits: X-ray: NASA/CXC; Ultraviolet: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSC; Optical: NASA/STScI (M. Meixner)/ESA/NRAO (T.A. Rector); Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech/K. Su

When a star like the Sun runs out of fuel, it expands and its outer layers puff off, and then the core of the star shrinks. This phase is known as a “planetary nebula,” and astronomers expect our Sun will experience this in about 5 billion years. This Helix Nebula image contains infrared data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope (green and red), optical light from Hubble (orange and blue), ultraviolet from NASA’s Galaxy Evolution Explorer (cyan), and Chandra’s X-rays (appearing as white) showing the white dwarf star that formed in the center of the nebula. The image is about four light years across.

Three of these images — SN 1987A, Eta Carinae, and the Helix Nebula — were developed as part of NASA’s Universe of Learning (UoL), an integrated astrophysics learning and literacy program, and specifically UoL’s ViewSpace project. The UoL brings together experts who work on Chandra, the Hubble Space Telescope, Spitzer Space Telescope, and other NASA astrophysics missions.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/chandra

|

|

|