The coconut palm — a graceful tree that shades tropical beaches and thrives wherever the climate is warm and moist — is a source of materials used to build rural houses and to serve as mooring poles for fishermen’s boats. Coconut is also an ingredient used in the preparation of Thai food. But for Thais, the coconut palm is a cultural icon — a tree which plays an important role in their way of life.

There are many ways in which the people of Thailand use the coconut in connection with traditional beliefs. When a family builds a house, for example, it is customary to plant a coconut palm at the eastern corner as it is believed that this will bring happiness to the household. And in fact it should have a beneficial effect by providing cool shade when the sun rises in the morning.

In both Buddhist and Brahman religious ceremonies, young coconuts must be included when offerings are made. Coconut juice is very pure and therefore deemed suitable for presenting to deities.

But when it comes to making practical use of coconut palms, Thais derive full value from the plant. The fronds, fruit and trunk all have their uses. Coconuts are grown both in orchards and on much bigger plantations. Commercial cultivation is concentrated in the Central Thai provinces of Samut Sakhon, Samut Songkhram and Phetchaburi, and extends south into Prachuab Khiri Khan, Chumphon and Surat Thani. Some farmers grow them exclusively, while others cultivate palms among other crops — as was generally the way in the past. On some very old farms in Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani and Nakhon Pathom, many different kinds of trees and plants can be seen growing together.

Vegetation is categorized according to height into three types, and taller growths play their part in the ecological system by providing shade to lower ones. The tallest include coconut and areca palms, and santol, tamarind and thonglang (a local species) trees. The mid level is made up of durian, mangosteen, banana, mango, orange and lime trees. Lowest of all are herbs and kitchen garden plants.

Traditional Thai households have gardens where plants are grown for domestic use. Bamboo stands and mango trees are usually included together with bananas, areca and, almost always, coconuts.

There are a myriad ways in which Thais make use of the versatile coconut palm. When a temporary shed has to be put up for storage or as a place to work, palm fronds woven into thick, multi-layered matting can be used for roofing and walls. The fronds can also be woven into a convenient shape and size to make a basket for carrying fruit or other goods. When sweets are wrapped in banana leaves during preparation, the packets can be fastened with coconut palm leaves to make them keep their shape during steaming. Once the cooking is finished, the palm leaves add to the attractiveness of the desserts and lend character.

Mature coconut palm fronds which have dried and turned yellow are also useful. The leafy matter is stripped away leaving the stiff mid-rib, which can be burned as fuel instead of firewood. They can also be tied together at one end to make a broom – the classic Thai broom used since pre-Bangkok times. Some street sweepers in the capital still use coconut frond brooms today.

As for the coconuts themselves, the older they get, the more useful they become. The husks can be burned to roast food, with the smoke imparting a delectable aroma and flavour to fish and pork. They can also be cut into small squares to make one of the best growing media for potted orchid plants.

In the past, Thais taught their children to swim in rivers and canals using life preservers made from coconuts. Two of them were tied together leaving enough slack for the swimmer to slip in between. It was cheap and easy to make and would never sink.

The hard shell that remains when the coconut meat has been removed, called the kala maphrao in Thai, is incredibly useful. In the past the lower part of it, cleaned and polished, was used as a ladle. The top part usually has a single hole in it with indentations, or “eyes”, nearby. Usually there are two of these eyes, but there are a few — very few — that lack the hole and have only one indentation. These “one-eyed” coconuts, as they are called, are extremely rare. A pile of coconuts as big as an Egyptian pyramid might contain just one of them.

These are considered to be highly significant at Buddhist temples and by amulet makers. The one-eyed coconut will be broken into many small pieces and carved into Buddha images or other sacred images. After being ceremonially consecrated, they are revered as important images with great power.

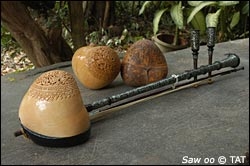

Big coconut shells are made into the body of the saw oo, a Thai stringed instrument. The more perfectly round the shell, the finer the sound of the instrument.

These are still not all of the uses that Thais have found for the coconut shell. If its upper part, the part with the hole, is cut off and polished it can be used to make a water clock to time cockfights. The way it works is to set the shell afloat; as the water seeps in through the hole, it gradually fills and sinks. As a timer, this is a very accurate and consistent device. It was used before clockwork or battery-operated timepieces appeared, and is still used today.

The meat from mature coconuts is simmered to extract coconut oil, which has a great many uses. The first and most familiar is fuel for lamps and lanterns. In the days before electricity, Thais had two sources of nighttime illumination: tallow candles and oil lamps. There is evidence that oil lamps have been used in Thailand since the Sukhothai era, more than 700 years ago. Earthenware lamps have been excavated from the ancient city of Sukhothai and from the ruins of other cities from the same period.

Among the items that have been dug up at these ancient sites are plates, bowls, cups, doll-like ceramic figures, small Buddha images and many oil lamps. The oil used in them must certainly have been coconut oil, as no historical evidence exists to show that any other kind of fuel oil was imported during in Sukhothai times or later.

Coconut oil also found use as an ingredient in herbal medicines, and for massage therapy. In the past, women liked to use it to make their hair shiny and lustrous. Although the trunk of an old coconut tree is less useful, people still find ways to put it to work. Villagers in seaside areas have long made pillars from it for their houses, and used it to make piers for mooring fishing boats.

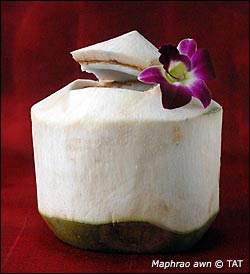

Coconuts also play a vital role in Thai cuisine. A fully-grown coconut palm produces nuts constantly, and Thais know how to make use of them at all stages of their development, from their tender beginnings to the last stage of maturity. A young or unripe coconut, called maphrao awn in Thai, is a fine fruit for snacking. All that has to be done is to take it from the tree and cut it open. When guests arrive one way to give them a warm welcome is to serve some tender coconuts, full of sweet juice and tender pulp. No one will refuse.

As coconuts mature beyond this tender stage, the meat becomes thicker and firmer, and can be used to make sweet snacks and desserts. For example, it can be shredded and sprinkled over dishes like rayrai, an old-fashioned Thai sweet in which tender, steamed, noodle-like strands are topped with shredded coconut sprinkled with sugar, sesame seeds and coconut cream.

Some of these coconut desserts are simpler, like boiled banana or pumpkin squash cut into thin slices and sprinkled with shredded coconut and sugar. The coconut adds a nutty flavour and delicious aroma.

But it is the fully mature coconut, with its hard, almost woody meat, that is most essential to Thai cuisine. The coconut is shredded and then squeezed to extract the coconut cream that enriches a great repertoire of Thai dishes. A wide variety of curry dishes, from spicy Kaeng Phet red curry to less aggressive ones like Tom Khaa Kai or Chicken Galangal Soup rely on it for their distinctive identities.

In preparing dishes such as these, the cook begins by adding a small amount of water to grated coconut to obtain two types of coconut liquid — a thick cream that is extracted during the first squeezing of the coconut followed by a thinner milk as more water is subsequently added.

The first step in preparing the curry is to stir-fry the meat in curry seasonings until it is tender enough to cut with a fork. Next, gradually add the coconut milk and leave to simmer until the meat is cooked. The coconut cream is then added to the curry. This gives the dish its fragrance and fresh flavour.

Coconut cream that has been simmered until it is very thick and then poured over the steamed, curried fish packets, called haw moke, enriches their flavour. Coconut cream is added to a number of yum (also spelt yam) Thai salad recipes for the same reason.

Coconut cream is an essential ingredient in many Thai desserts. In fact, so many dishes, both sweet and savoury, require coconut in one form or another that its place in Thailand’s culinary culture lies very close to the centre.

In a traditional process, coconut cream was simmered until the oil separated out. This was the only cooking oil available in the ancient days of Siamese cuisine. In the South, fish are coated with turmeric and then fried in coconut oil to bring out their delicious aroma.

Fried fish dishes of the Central Region also use coconut oil. Fried banana fritters called kluay khaek are best when coconut oil is used to fry them.

About 40 years ago, the popularity of coconut oil in Thai cooking began to decline. There were two reasons for this. One was the increasing availability of other kinds of vegetable oils for the kitchen. The other was that coconut oil made by simmering coconut cream did not keep well. If stored for a period of time, it developed a rancid odour.

But recently coconut oil has been enjoying a comeback. Scientists have established that it is very healthy, and now that ways of producing it without using heat have been developed it is purer and retains its fresh aroma. Coconut oil made in this new way is also excellent for massages and as an ingredient in cosmetics.

A great variety of herbs and plants feature in traditional Thai culture. But none is closer to the heart of the Thai way of life than the common coconut tree.