Thailand’s water culture inspires one of the country’s most popular and picturesque festivals, Loi Krathong. Upon the full moon of the twelfth lunar month each November, millions of Thais light the waterways with ornate floats or spangle the skies with fireworks and paper lanterns. And wistfully make a wish.

Regional Variations

This well-preserved ancient tradition differs around the kingdom and many travel to see the distinctive regional celebrations.

The generic krathong (leaf vessel) that people loi (float) is a raft of banana stem adorned with leaves, flowers, incense and candle. Found nationwide, it is best exemplified in the major celebrations in Bangkok, the capital, and Sukhothai, an ancient former capital. People in Tak province make Krathong Sai using multiple coconut shells strung together. Curves of banana stem ‘bark’ are used to form the simpler Krathong Sai Kaab Kluay of Samut Songkram. Lanterns in the North float in the sky instead, with flame-powered Khome Loi paper balloons lofting upwards most dramatically around Chiang Mai in the North.

Evolution of Loi Krathong

The festival’s roots are ancient, but the Loi Krathong we see today became popularised from palace rituals of the early Rattanakosin era to venerate the water goddess, Mae Khongkha.

Two centuries ago, most Thais lived on rafts or in waterside stilt houses. Water was vital to livelihoods from fisheries, floating markets and rice fields. It is not by coincidence that Loi Krathong occurs at one of the year’s highest tides.

What is a Krathong?

The festival materials reflect a bygone village lifestyle. A krathong raft uses a buoyant disc of soft banana tree trunk ringed by banana leaves folded into auspicious traditional Thai patterns known as Lai Thai. The standard shape resembles the open petals of a lotus in bloom. Other rafts peak in the middle to evoke chedis (stupas) or the mythic Mount Meru. Some take the form of a sacred swan. Each krathong contains the Buddhist offerings of flowers, at least one incense stick and a candle, the flame and glowing ash fading as the vessel bobs downstream.

New Eco Designs

Contemporary taste and materials have influenced krathong design. Creativity with petals and leaves turn floats into works of art. Natural dyes add to the floral palette. A fad for polystyrene bases has given way to greater awareness of their adverse environmental impact. Traditional vessels are biodegradable, but that still takes time. An ecologically-sensitive krathong can now be made from bread or vegetable matter which fish can eat.

Beliefs Behind the Rite

The increasing quantity of krathong each year begs the question why Thais create them in the first place. They are an offering not just of thanks for life-giving water, but an apology for polluting or carelessly misusing the pristine gift of the Mother of Waters. Municipal workers collect all the spent krathong they can, while some Thais minimise their impact by sharing with friends or family.

The festival is a chance for communal sanuk – the Thai sense of fun. Thais flock to the waterways in gleeful, larking groups. Couples often launch one jointly as a romantic gesture of togetherness. Those seeking better luck place something of their own – a hair, a coin, a nail clipping – into the raft, because the act feels like casting away one’s grief or ill-fortune. People bow down with the krathong raised to their forehead, pray in thanks, then set the craft adrift.

The Origins of Loi Krathong

How the festival began remains unclear, but various accounts point to an Indian origin. The closest parallel is with Deepavalee, a festival of lights also held in November, in which Hindu devotees float tiny lanterns to honour the gods Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu. Other authorities speculate that it may derive from an act of remission to India’s sacred River Ganges.

Buddhist explanations of Loi Krathong suggest a rite to honour the disciple Phra Uppakhut, or to pay respect to the Lord Buddha’s footprint beside the mythical Narmada River.

An ancient Thai tale holds that the krathong was invented in the early Siamese kingdom of Sukhothai by the maiden Tao Sri Chulalak, commonly called Nang Noppamas. Beauty contests held around the festival crown the winner as Nang Noppamas, who typically then leads a festival parade in Siamese costume.

Given their traditional river-based lifestyle and culture, Thais expressed gratitude to Mae Khongkha, the Mother of Waters, their equivalent to the Hindu goddess of water. Offerings to her evolved into the Loi Krathong ritual of thanks, and also of appeasement. Thais beg her forgiveness for carelessly polluting the pristine water that sustains all life. Over time the festival spread throughout the country.

A national event

Loi Krathong is not a public holiday, but it’s marked on every calendar. No visitor could miss it, since almost every Thai takes part. Festive decorations fill shops, hotels and public spaces, which resound to retro recordings of the familiar old Loi Krathong song. Planes, trains, boats and roads all become packed with revellers travelling to the nearest pier or to the showpiece events.

REGIONAL VARIANTS OF LOI KRATHONG

SUKHOTHAI LOI KRATHONG AND CANDLE FESTIVAL

At the Sukhothai Historical Park,

November 8 – 10, 2011

Sukhothai becomes the focus of national celebrations. Fireworks, processions, cultural events, a candle festival and a sound and light show take place around the Sukhothai Historical Park, a World Heritage Site (see below). Giant lanterns in creative shapes get mirrored in the temples’ reflecting pools, where visitors glide their own krathong.

LOI KRATHONG SAI FESTIVAL

THE ROYAL TROPHY LOI KRATHONG SAI, TAK PROVINCE

Night of A Thousand Floating Lanterns

On the Mae Ping River (in front of Kittikhun Hall), November 9 – 12, 2011

Tak province, near Sukhothai, holds its distinctive Loi Krathong Sai Festival (see below). Sai means ‘string’ and refers to the way that scores of krathong float in long chains down the Ping River. The krathong, too, are different, being made from coconut shells threaded together.

LOI KRATHONG SAI KAAB KLUAY MAE KLONG

At the Rama II Park and Wat Chonglom temple in Samut Songkhram province

November 10, 2011

Samut Songkram (also known as Mae Klong)

recently revived its old Loi Krathong Sai Kaab Kluay tradition (see below). Residents of this western coastal province don’t make krathong out of a disc of banana stem, but carve layers of the cellular stem into plate-sized rounded oblongs that curl like tree bark. A resin-dipped stick of incense pierces the middle like a mast, with a bloom of dao ruang’ (marigold) on each end for balance. In contrast to the opulence of krathong elsewhere, these sail down the Mae Khlong estuary with thrifty simplicity.

THE NORTHERN LANTERN FESTIVAL &

YI-PENG LOI KRATHONG

Chiang Mai provincial centre,

November 8 – 11, 2011

Chiang Mai hosts the north’s distinct equivalent festival, Yipeng (see below). The event lasts several days on a far larger scale, with two road processions, river races, a lantern festival, traditional displays and cultural performances. Firecrackers whiz and bang throughout.

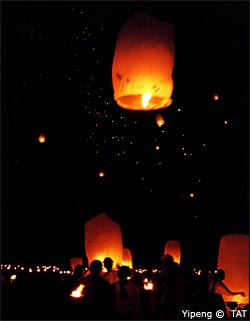

Northerners do launch krathong floats, but favour releasing paper lanterns, which they send skyward by igniting a waxed paper burner. Called a Khome loi (floating lantern) or khome yipeng, these are tissue-thin bags the size of a refrigerator. To fill each with hot air takes the help of three or more people, so it becomes a shared experience. The lanterns drift thousands of feet up on swirling air currents, often trailing a sparkler. Some groups organise simultaneous massed releases of khom loi, a spectacle of jaw-dropping beauty.

Folk Entertainments

Loi Krathong heralds the start of the outdoor festival season. With the rains over, the fresh, balmy nights witness many fairs at temple grounds and open spaces. Bangkok’s most famous temple fair surrounds the Golden Mount at Wat Saket for ten days around Loi Krathong. Another fair enlivens Wat Liam by Memorial Bridge.

Countrywide, Loi Krathong fairs feature traditional pastimes and performances, outdoor movies, stalls of goods and speciality foods, not to mention Nang Noppamas beauty contests. At this time of renewal, many Buddhists at temple fairs receive blessings on their forehead in the form of daubed paste or gold leaf.

How to Participate

Visitors can easily get swept up in the merriment. Most hotels stage Loi Krathong parties at their poolside. Those willing to brave the waterside crowds can buy a krathong of their choice from stalls for between 50 and several hundred baht, depending on how elaborate the design. Vendors in the north and many beach resorts also sell khome loi lanterns.

Make Your Own Krathong

For the most authentic experience, anyone can make their own krathong . Fresh markets sell all the materials. Pick a cake-sized slice of banana stem (yuak kluay) as the base. Buy a few sun-softened banana leaves (bai tong) to tear into rectangular sheets. With a template or help from a Thai friend, fold these into flame-like twists (jeeb krathong) and pin them round the rim with slivers of bamboo. In the middle, arrange flowers like lotus bud (dok bua), rose (dok kularb), marigold (dok dao ruang) or globe amaranth (dok baan mai rue roi), a never-wilting symbol of eternity.

Light the candle and incense, make a wish, set your krathong on the water, and nudge it downstream with a gentle punt. Making your own krathong personalises the festival and emphasises the sense of letting go the negative, with thanks for nature’s sustainable bounty. Seeing your krathong or khome loi disappearing into the distance feels like a wistful act of closure, creativity and renewal.

* Note as of 9 November 2011

Some Loy Krathong events in Bangkok, Ayutthaya and Suphanburi have been scaled down to reflect the traditional elements of the festival due to the flood.