|

A trip out of town -

destination Buriram

by Lesley Warner

Day One: It was a long weekend

so I decided on another trip to Buriram. This time I had my prized

possession, my new car with its low profile alloys. I called into a garage

to get my tyre pressures checked and looked in concern as the air gage went

up to 40. The garage attendant argued that this was correct but fortunately

I decided to ring my mentor Dr. Iain (Pattaya Mail) for advice and he

told me 22-26, so be warned, check your air pressure!

A

nice place to cool off A

nice place to cool off

I hardly need tell you how a car this low took to the

country roads. As we turned into the road leading to the village, we looked

in amazement at the pile of dirt blocking the road; it was about 2.5 meters

high and had obviously been there for a while. It looked quite solid but

before I had a chance to comment my driving companion decided to go for it.

The noise was horrible as the wheels dragged the body of my poor car across

the dirt.

I was ready for the inevitable drink that was put in my

hand when I got to the house. By about 2 a.m. everyone decided food would be

a good idea, this in my mind was a nice restaurant, but we drove several

kilometers into the wilderness. There in the darkness was a solitary light

shining. The car stopped, I could see a man standing alone by a wooden

table, and on the table, glistening in the reflection from the light, was

the carcass of a buffalo freshly slaughtered. In his hand the man had a

large knife and was carving slices from the carcass. One of the lads asked

me for 140 baht and off he walked towards the man. Someone in the back of

the car whispered “do you want to look?” I said “no thank you.”

It’s

now or never It’s

now or never

As he came back towards the car through the darkness, the

bag in his hand broke and the blood spilled onto the road. Someone said a

ghost was jealous and wanted the blood, and by this time I was ready to

believe anything.

When we finally arrived home we lit a barbecue for the

meat, but the bag also contained a section of the intestines tied at each

end. One end was undone and the liquid inside was squeezed into a bowl with

some blood and chili powder. Then the liver and other unrecognisable parts

of the innards from the bag were consumed raw. At this point I retired to my

bed.

Day Two: The next day we decided to go and see some

of the celebrations the locals were putting on for Khao Pansaa.

Unfortunately we had missed most of the celebrations, which were held the

day before, so we went to Phimai in Korat and looked around the ancient

temple and the grotto of Banyan trees called Sai Ngam. Banyan trees there

cover more than 35,000 square feet – some are over 350 years old.

It’s a strange and interesting place to look around if

you are in the area. There are lots of interesting and very cheap souvenirs

to choose from, and I bought some traditional musical instruments. One was

named a Kaan, which was made from bamboo, and one of the local men played it

for me when we got back to the house.

Tat

Ton waterfall Tat

Ton waterfall

On the journey home, due to the lack of rain in Buriram

this year, we saw only fields of hard dry earth instead of the usual

patchwork of green rice shoots sprouting from the watery landscape. This

means that the rice has to be scattered on the dry earth rather than planted

neatly in the water by hand, making it much harder to cut later. If rice is

not planted the area can suffer for up to 3 years meaning the people have

less to eat and no money.

Maybe understanding this makes it easier to see why they

eat things that we think are disgusting. Also why it’s preferable to work

in a bar in Pattaya than struggle to find enough to eat while you sit

waiting for the rain that doesn’t come. That could be why there is a

noticeable lack of women in the villages from 18 - 25. When I asked why I

was told, “They work away”. Hence the reason my drinking companions in

the family are all men in this age group; poor guys have lost all their

ladies.

Wat

Ban Rai Korat Wat

Ban Rai Korat

Later in the evening we went to see some family friends.

I sat down near a bucket, and as I glanced into the bucket I could see the

contents moving as one, but in actual fact there were hundreds of shiny,

fat, red bugs. Someone said to me, “You can’t eat them yet, first they

need to be cooked.” So they promptly went away and fried them. The bowl

was then put in front of me. I said, “I’m not really hungry, thank

you.” When pushed to try them I had to decline. I have tried bugs before,

but these were just so fat and juicy! They peeled them like monkey nuts and

ate the inside.

Then I just happened to say, “Where do you find

them?” Before I knew what was happening I was bundled into a pickup with 5

men, lights on their heads like miners use, and we were bumping down a dirt

track into the pitch-black jungle. As I wandered around the jungle following

and observing the enormous effort put into catching one single bug several

meters up a tree, I thought how lucky I was once again to witness this.

After all I could be in England sat watching East Enders on TV, instead of

in the jungle in the middle of the night with a sleeveless shirt and

flip-flops and in charge of putting the bugs in the bottle.

Is

this what we’re looking for? Is

this what we’re looking for?

Day Three: We set off early in the morning without

breakfast, as it appeared to be only bugs on offer again. We decided to go

and see the famous monk near Korat in Wat Ban Rai called Rhongporkhun. He is

one of the monks whose image is hung in the car to ensure a safe journey.

The reason, I was told, is because there was once a plane crash and all the

people died except those carrying the symbol of Rhongporkhun. Now, to be

blessed by him is very special and people come from all over Thailand to see

him. I was fortunate to be one of these. As I knelt down in front of him, I

got a sharp rap over the head with his baton. The architecture of the Wat is

quite beautiful and although small, worth seeing.

I would like to say a special thank you to a very honest

Thai lady. While visiting the toilet at the temple I dropped my purse. This

lady came and found me to return the purse fully intact; can you imagine my

plight to be so far from home with no money or credit card and not enough

petrol?

Day Four: We made our way to one of the national

parks in the area, Tat Ton and went to look at the waterfall. The lack of

rain was noticeable and unfortunately the waterfall was reduced to a

minimum. They are building some very nice bungalows among the trees, for

tourists. The cost for 4 people is 800 baht and 10 people 2000 baht. They do

river rafting and helicopter rides; also within the parks there are caves,

butterflies and many beautiful flowers. It’s a nice place with a tranquil

setting to visit for a quiet few days holiday.

The 201 goes to Bangkok but we decided to go back to

Korat, then home via the hill pass at Kabin Buri - big mistake. Nature in

her wisdom had decided to drop all the rain that should have been shared

between Buriram and Korat on the hill pass. We witnessed people’s misery

and their laughter as the water swept through the houses relentlessly. As we

drove we realized we were fighting time and soon the road would close. There

was no turning back; if we didn’t get through we would be stuck and

probably sat ‘atop’ my prized possession. As we had thought the road was

flooded but the police waved us on. I closed my eyes and prayed as we went

through.

Thank you Rhongporkhun, your blessing obviously worked

and we got home safe and sound after another eventful trip to the beautiful

North East of Thailand.

Cactus Badlands;

America’s Kingdom of Sun-fire

by Chalerm Raksanti

Thus described by American bard, John c. Van Dyke, the

Sonoran Desert; those 120,000 square miles of desolation, which stretch

across the southern part of the American state of Arizona, California,

Colorado River Delta, and deep into the Mexican state of Sonora, and the

peninsula of Baja California.

Baddest

of the badlands, the Cerro Colorado crater, one of a dozen in the Pinacate

wilderness of Mexico’s northern Sonora Desert Baddest

of the badlands, the Cerro Colorado crater, one of a dozen in the Pinacate

wilderness of Mexico’s northern Sonora Desert

The desert, anywhere, has always been a place to avoid,

or to overcome. Native Americans survived in the Sonoran by gathering plants

and hunting deer and bighorn sheep. In the late 1600’s Jesuit priests

introduced a new god, and a new crop: wheat. In the 20th century, irrigation

projects have allowed cities to flourish. Although still hot, parched, but

spouting with life, the Sonoran Desert in both the USA and Mexico opens its

arms and the desert blooms. Population growth is pushing land-use and water

issues. And with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),

the desert will change even more. This region is going to be either formally

protected, or commercially developed. It’s former isolation and aridity

will not protect it in the future.

Cowboys

in the Sonoran have been a way of life for more than three hundred years Cowboys

in the Sonoran have been a way of life for more than three hundred years

The major cities of Tucson and Phoenix and their

sprawling suburbs make the fragile balance of life and death in the desert

seem irrelevant. Phoenix lies in the valley of the Salt River, in a natural

desert cycle of drought and flood, but in the late 1800s Anglo pioneers

lobbied the American government to build the Roosevelt Dam, which was

finished in 1911. When modern Phoenix rose, the city fulfilled a peculiarly

American dream; creating something out of nothing.

Arizona’s other urban pillar, Tucson, seems more in

tune with the desert, and uses local trees and plants to landscape gardens

and parks.

But as more people pour into the ‘Sunbelt’ these

cities will mutate into something like Southern California, an artificial

land of green lawns and shade trees.

The Sonoran is one of four North American deserts, along

with the Great Basin, the Mojave, and the Chihuahuan, and for the most part,

the Sonoran still seems vast and untrammelled. One of the largest intact

arid ecosystems in the world, it shelters endangered animals such as the

Sonoran pronghorn and the lesser long-nosed bat. And because it has rainy

seasons in both summer and winter, the Sonoran is the world’s most

botanically diverse desert, with more than 2,500 species of flora.

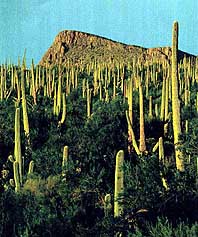

The

saguaro cactus, the silent sentinel of North America’s Sonoran Desert The

saguaro cactus, the silent sentinel of North America’s Sonoran Desert

Among a collection of plants that seems straight from the

imagination of Dr. Seuss, the star of the desert is the saguaro cactus. This

is the enduring symbol of the state of Arizona, and it reaches the heights

of 50 feet or more, weighs tons, and lives as long as 200 years. The saguaro

grows only in the Sonoran, and its forests march up mountain slopes like

determined soldiers. This cactus is so personable, with its chubby arms

often set in a ‘hands up’ look, that desert American Indians often

remark its just another type of human being. Like a man, the saguaro has an

internal skeleton covered with pulpy flesh. When a saguaro arm is chopped

off, it seems like an amputation. But the desert is also full of things that

stink, sting, bite, prick, and grab, as well as things which are armed and

dangerous, including the cactus thorns, the rattlesnake, and scorpions.

About 60 miles west of Tucson, where the Coyote Mountains

rise from the scrubland of mesquite, Kitt Peak National Observatory looks

heavenward, and Route 86 enters the Papago Indian Reservation - 2.5 million

acres flattened against the Mexican border. This is home to 6,000 Papago, or

Tohono O’odham, (desert people). For centuries five Indian nations

dominated the desert. Apache wandered in the mountains to the east, Pima

lived in the river valleys of today’s Arizona. Seri fished and hunted sea

turtles on the Gulf of California, and the Yaqui farmed the river deltas in

Sonora. The Papago and their related bands lived in the desert. Each winter

they migrated to villages in the desert foothills, and in summer they

returned to the lowlands. The Indians hunted and gathered desert food,

cholla buds, mesquite pods, prickly cactus pear, and saguaro. Certainly

these people were masters at desert living, but when the rains failed, they

sometimes starved. In 1854 the division of the USA and Mexico split the

tribe, and the US government established a reservation which ended their

migratory life.

Tucson,

Arizona, popular destination for retirees and Americans fleeing the

snowbound months of winter. Tucson,

Arizona, popular destination for retirees and Americans fleeing the

snowbound months of winter.

Jesuit priests established 25 missions in the desert

between 1687 and 1711. The missionaries and other Europeans introduced

livestock, horses, figs, barley, wheat and fruit trees. Sonora today is

still a rugged livestock culture of cattle ranches, horse races, straw hats,

and cowboy boots. But many southern Mexicans from Chiapas have moved to

Sonora for jobs in farming and industry. And so the culture is being

altered.

The unique landscape of the Sonoran Desert’s dunes,

pine forests, scraggy buffalo grass, cactus and spacious skies evoke a

simple wisdom; arid land has limitations. It can be an oasis, a promised

land. Yet it needs protection from overpopulation and abuse. Therefore, much

of the Sonoran in Arizona still belongs to the Great White Father in

Washington DC (the federal government). It is arguable that military

stewardship has probably preserved the desert better than others might have

done, by limiting access to the public and land developers. Things are

changing in this desert, and they are changing fast. But there is still time

to pay homage to this landscape filled with beauty and silence.

Updated every Friday

Copyright 2001 Pattaya Mail Publishing Co.Ltd.

370/7-8 Pattaya Second Road, Pattaya City, Chonburi 20260, Thailand

Tel. 66-38 411 240-1, 413 240-1, Fax: 66-38 427 596

Updated by

Chinnaporn Sungwanlek, assisted by Boonsiri Suansuk.

E-Mail: [email protected]

|

The Rotary Club

of Jomtien-Pattaya

Skal

International

|